This blog post will explain the approach we used in MutableSecurity to add minimal, non-intrusive application monitoring, for both crash reporting and usage monitoring. Despite the examples from our codebase, that is mostly Python-based, the principles used may be applied with ease to other programming languages.

Why Metrics are Important

The quote “What gets measured gets improved” is mostly used to highlight the importance of having quantitative measures of performance about a system. Whether it was said by the influential management consultant Peter Drunker back in the previous century, there are some situations in which these numeric metrics help us to better understand a system's functioning. In the software field, examples may be finding out how many users you have, how they use your program and how the product behaves regarding performance.

In addition, there may be another piece of the puzzle left: the survivorship bias. Simply said, history is written by the victorious. Applied to the software industry, we can say that we tend to judge the overall experience of our products by interacting with the users or customers (via feedback forms, interviews, etc.) that are active today, not those who abandoned the journey due to encountered issues (for example, bad UX practices, bugs and errors). But we may learn about the latter category by implementing passive feedback loops.

Feedback Loops

For open source projects, we can have multiple places from which we can learn from and about our users.

There are active forms, in which the user can deliberately contact the project's developers to share an impression, request a feature, or report a security problem. They can create GitHub issues or, more privately, contact us through in-app forms or emailing to our addresses.

On the other hand, we have passive data collection. The user interacts as normal with the application, but he deliberately allows the collection of usage data: which UI elements he interacted with, difficulty of finding out a desired page and so on.

We can consider the app stores downloads too, but they are too opaque. For example, we could not know if the software downloaded through GitHub or PyPi (a Python package repository) was actually run. Or if the user only downloaded it, but found it hard to understand the workflow. To consolidate this argument, think about the Python ecosystem: bots (like Snyk's ones) are scanning the published packages in order to find vulnerabilities.

The Privacy Dilemma

But there's the catch 22: as software developers, we need to think profoundly about the privacy of our users. We can't collect all possible data. In the past years, due to many privacy issues events such as keylogging social media platforms and huge data leaks, people got more conscious about what data are collected by companies and how they are used afterwards. It can be said, for sure, that the trust of users was damaged.

Our Approach for Application Monitoring

To give a bit of context, we created a platform to automatically deploy and manage cybersecurity solutions. At the first step, we published on GitHub a CLI tool to achieve these goals. The hardest part, now, is to determine what happens next after the download from PyPi is complete. Does the user deploy a specific solution? Or does he encounter an error and uses the software only once?

We reached a solution to these issues. We implemented a minimal, non-intrusive application monitoring system for MutableSecurity:

- Collecting usage data with Firebase Realtime Database and a serverless function, deployed on Google's cloud (Google Cloud Platform or simply GCP)

- Integrating an error tracking platform, Sentry

- Giving the user a method to opt out

- Documenting the whole monitoring process.

The following sections will describe each of them with a bird's eye view. All of them are exemplified with Python snippets from our codebase and screenshots.

Usage Monitoring

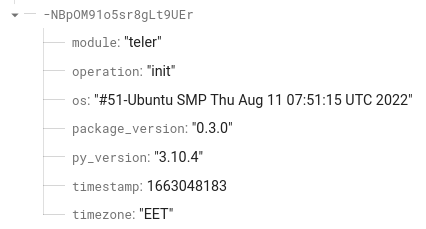

- Collect the data: We implemented a base abstract class named

Metric. Each collected metric should inherit it and overwrite theIDENTIFIERmember (that defines the key used to identify the information when placed in Firebase) and the_getmethod (that extracts the information from the current host). When a new metric is defined, the__init_subclass__method is used to automatically register it (by storing a reference in a list) in theDataCollectorclass, that deals with collecting all the metrics values.

- Send the collected data: The

Monitorclass is then used to retrieve all the metric values andPOSTthem to our serverless function.

- Retrieve the data and store it inside Firebase: The serverless function from Google Cloud Platform is configured to run in a Python environment, with a secret that is used to store the service account's private key. It only takes the data from the HTTP request and stores it inside Firebase Realtime Database with the

pyrebase4package.

Check Firebase for the collected usage data: In our case, the data looks similar to the screenshot below.

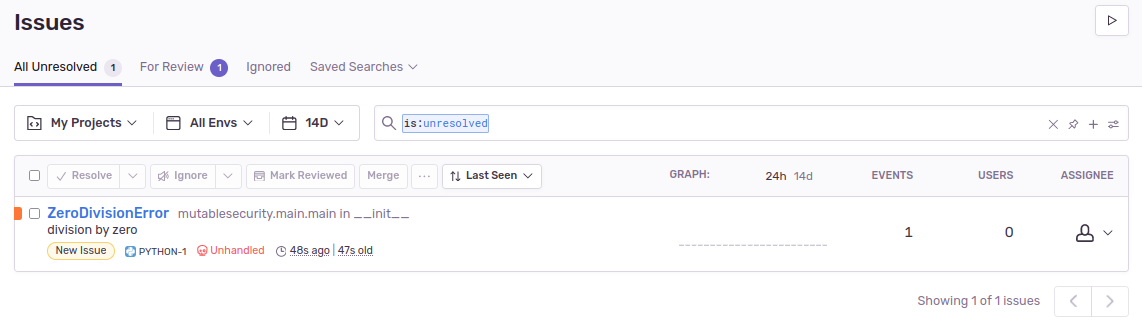

Crash Reporting

- Add the SDK: After setting up an account, install the Sentry SDK for Python,

sentry_sdk. - Initialize the SDK: In the source code, call the

initmethod of Sentry's SDK.

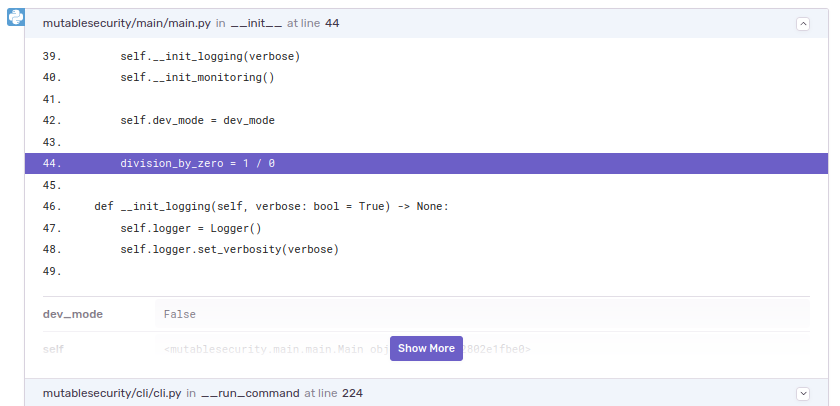

Trigger a crash: Just place a division by zero (for example,

1/0) operation between some lines of code that are certainly executed. Be sure to remove it afterwards.Find the crash in Sentry's dashboard: Sentry should list the triggered error. Alongside it, there are further details such as stack traces and runtime information.

Opting Out

Implements a logic to let the user opt out of the monitoring data. This can be achieved by adding a new aspect in the configuration. In MutableSecurity, we skip the logic presented in the Usage Monitoring section if the user sets a field in the configuration file.

Be Transparent Regarding the Monitoring

If you have read everything until this point, you are conscious about the benefits some data may have. Namely, to learn more about the users you want to help with your software. As the software user - developer relationship is one of a partnership, the main principle is trust, and it needs to be built and maintained. Also, it needs to be transparent about:

- Why you collect metrics at all?

- What metrics you collect?

- If a user wants to see the implementation, what files from your codebase are relevant?

- How can you opt out of sending any usage/crash data?

These questions may be answered with a page of your documentation or as a separate view inside your production software. You can see examples on Homebrew's and MutableSecurity's websites.

Conclusions

Having feedback loops is important for a software developer. The data may shift the focus from some functionality considered relevant to others that are actually used in the wild. This blog post explained the reasoning behind collecting data, some handy principles to keep in mind, and a Python implementation we developed for MutableSecurity. For further information about the development in the open source community (including metrics), I recommend following the GitHub's articles on opensource.guide.

Until next time!